Feelings data (+ important note)

important frontmatter note: after this edition of Data Curious I will be culling my subscriber list. This means that if you have never opened an email from me, you might be removed from the newsletter. I have never done before, but since moving to Ghost I have started to pay monthly fees past a certain number of subscribers. This is forcing me to think more "quality" than "quantity"—if someone has never opened one of these emails, they probably won't miss them and it's not worth me paying just to see a bigger number. Plus you can always re-subscribe. To be fair to newer subscribers, I will start removing readers with the oldest signup date who have never opened an email.

Heads up: this edition of Data Curious will be a little different. I want to share some takeaways from a recent workshop I hosted on data visualization and AI. Next time I'll get back to sharing links.

A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of hosting a workshop at PyData Vermont. I have given many talks about data visualization, how to make better charts, how to think about memorability and clarity, etc. But this time I wanted to do something different.

So I asked a bunch of data nerds to do something unusual: process your feelings about your work, using data and art.

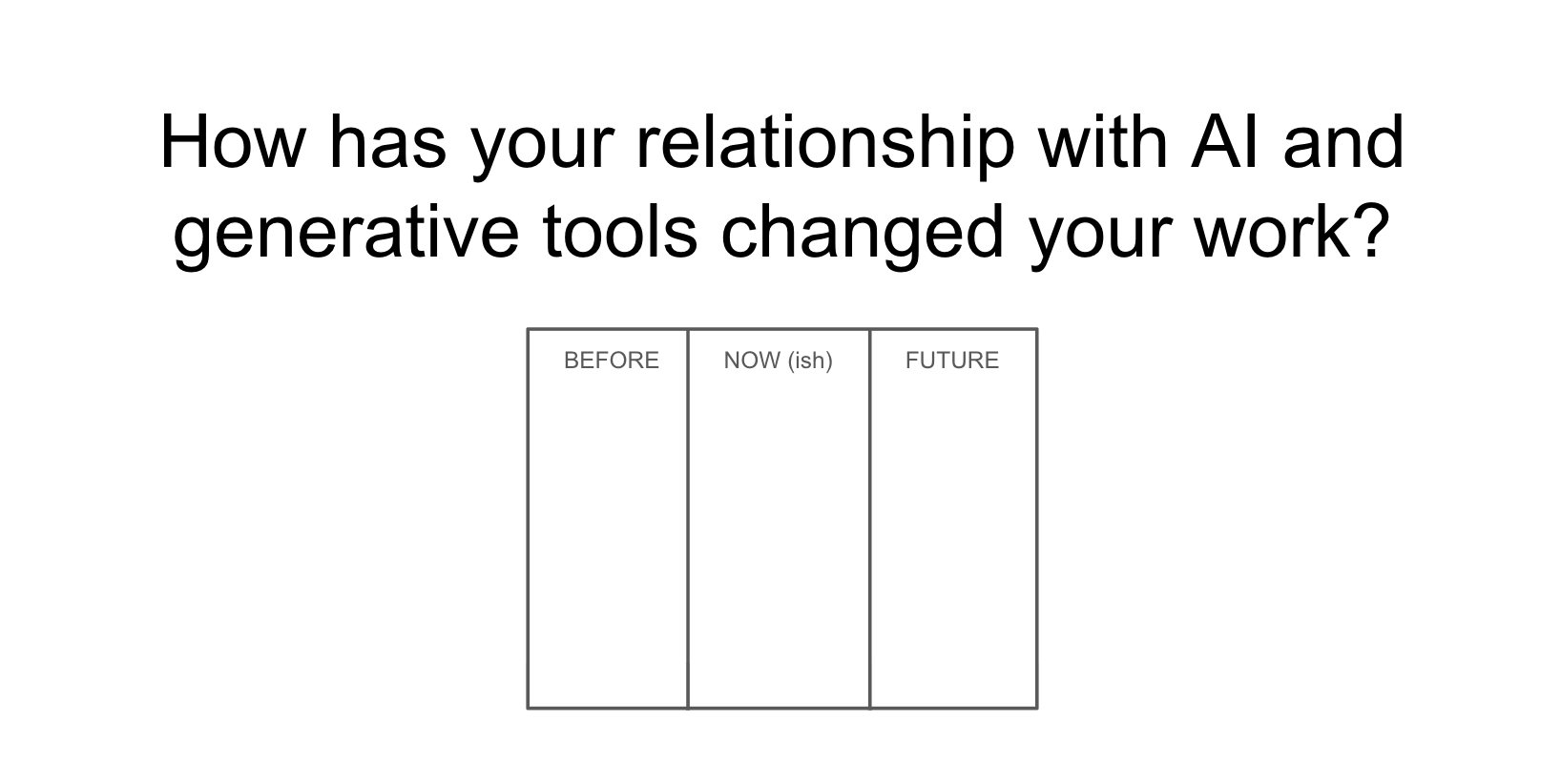

To be more specific, I asked them to think about their work before the rise of generative AI tools, their work now, and in the future. And I think it'd be fair to categorize what happened next as a group therapy session (I actually heard multiple people use this phrase as I walked around the room).

Keep in mind, this is a conference about Python and data. We had people in the room from some of the biggest software and hardware tech companies in America, all of which are deeply intwined with accelerating AI in the workplace.

Two things told me I hit a nerve. When I introduced the prompting questions to the group:

- a collective groan came forth

- multiple people asked that we stop recording this part of the session, for fear their employers would learn some of their true feelings about AI

The people in this building were using tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Co-pilot and more every day, and they have A LOT of complicated feelings about them. We talk so much about what AI tools can help us do, and not enough about "how do you feel when you use them?".

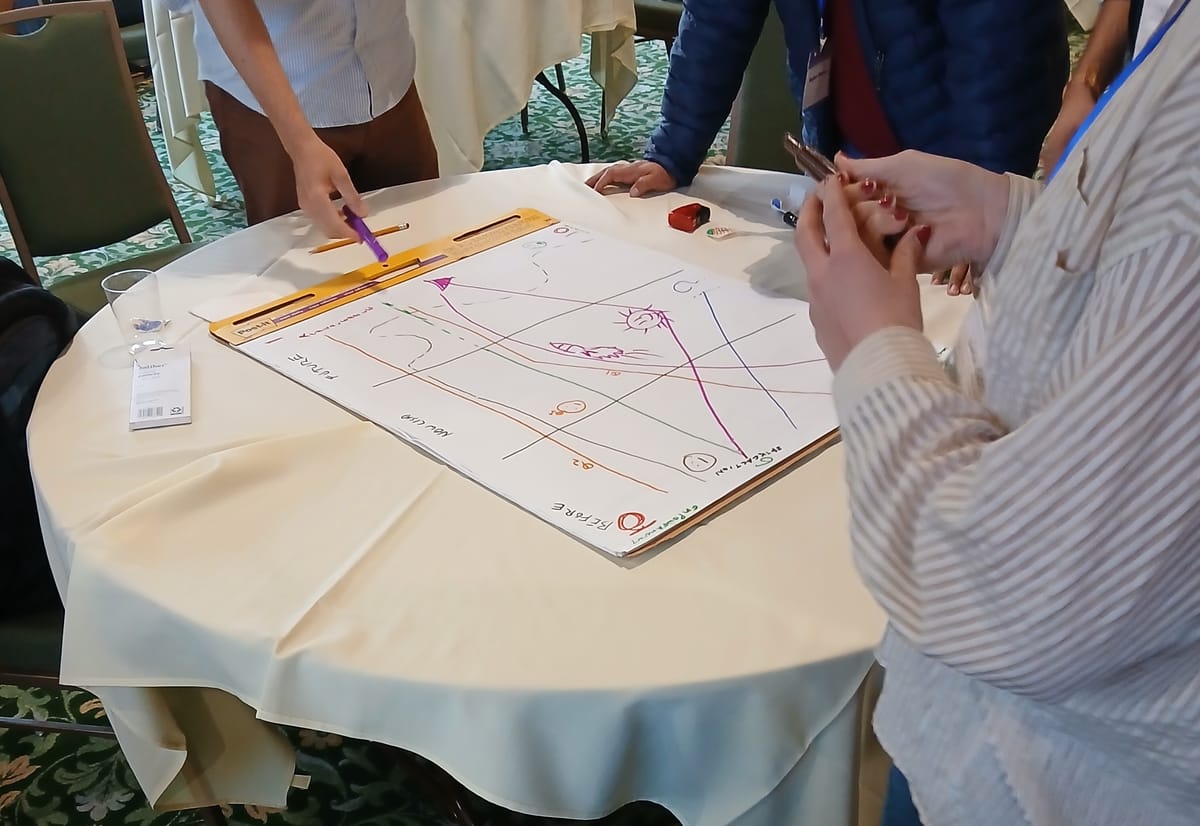

I wanted this to be a very tactile workshop, no screens allowed. I wanted people to have the experience of sitting around a table, talking through a complicated topic, and then creating something that visually represented how they felt about it. To get into what this "data humanism" mindset, I used one of Giorgia Lupi's previous Data Portrait activities as a bit of a template.

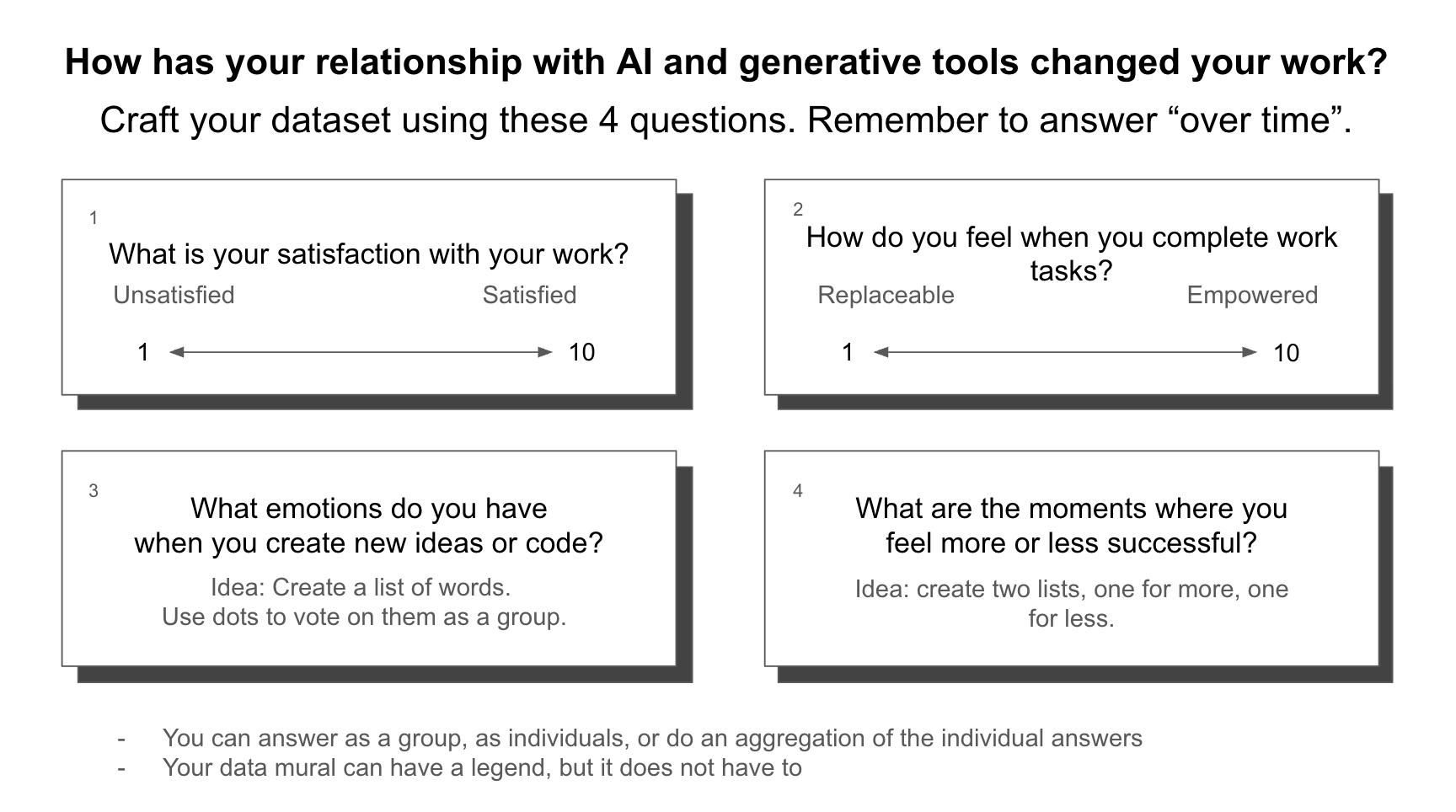

As a group, we answered some basic questions about ourselves and then used the ideas of "visual encodings" to think outside of basic charts and graphs.

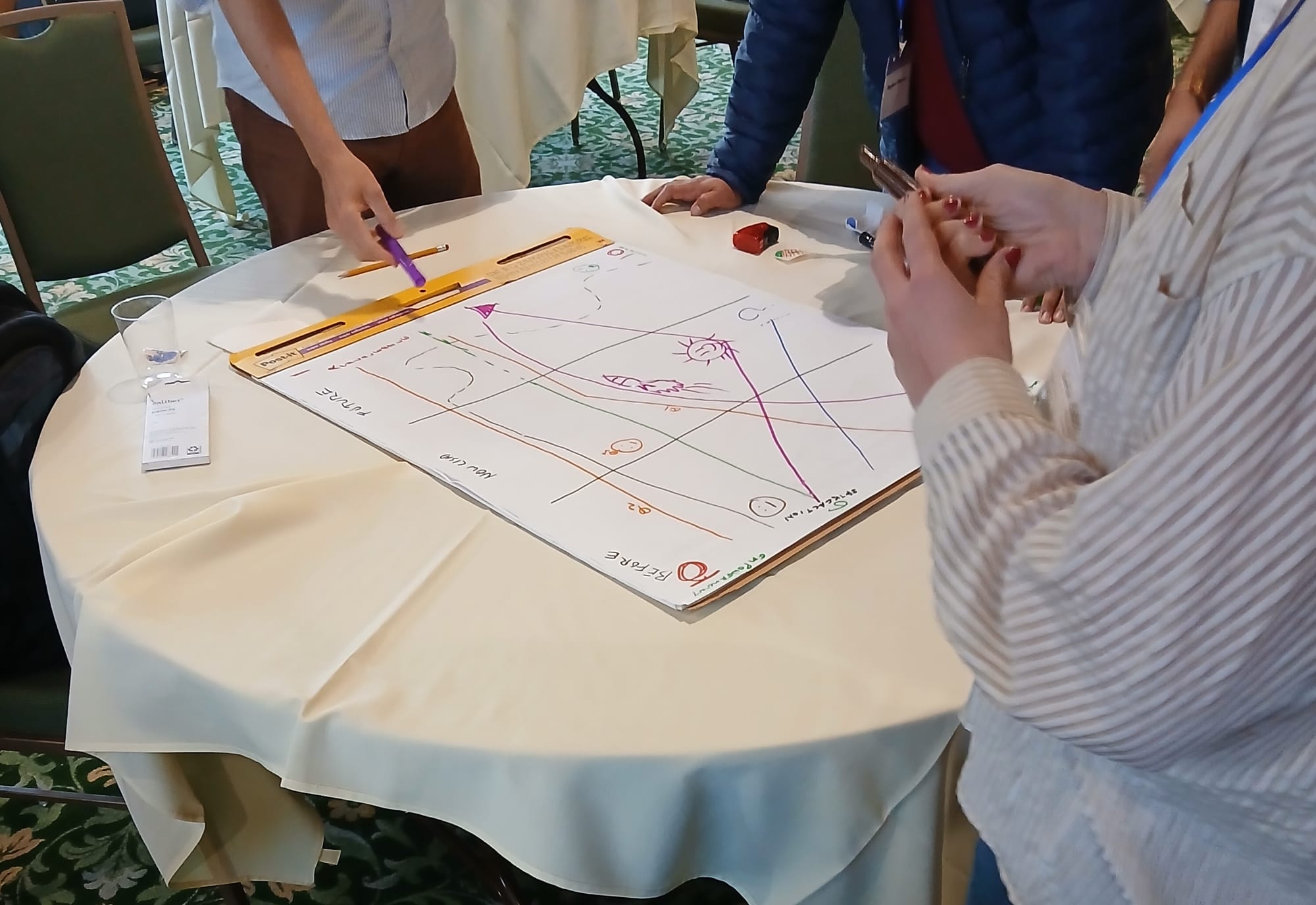

Everyone seemed to enjoy the activity, so much so that they began bending the rules a bit. What if I feel that the future is both grim and unknowable? what if my work is a passion and purpose? New combinations of lines, dots, colors, and shapes emerged.

And then it was time to get real. Now that everyone was in the mindset of hand-drawing data, we introduced a new survey to create a new dataset.

Each table had between 4-6 people and had 30 minutes to complete the activity. Honestly, that wasn't nearly enough time; people had a lot of feelings about this topic. And they drew these feelings on 4x3 posters, together.

In the remainder of this newsletter, I'll do my best to sum up a few observations on how this went. I had the privilege of being a fly on the wall here, walking around and listening to people process their feelings about using AI together as group.

Here's a few things I learned. As a clarifying note, I'll be using AI as a shorthand here for any chat-based LLM that helps you code, write, brainstorm, etc.

Workers (even tech workers) feel AI being pushed on them even when they don't want it

It's everywhere. It's in your Gmail, in social media, in VSCode. I don't remember when the tipping point came, but it feels like even a few months ago most AI-assisted tools were very "opt-in". You had to go find the extension or add the tool, and then you could use it. Now it's force fed.

The overall sentiment in the room was that AI was here to stay. This is despite the now viral MIT study that 95% of AI programs at companies are not delivering a bump in revenue. People felt it as an inevitability, but wanted to engage with it on their own terms, not their employers.

AI helps people do things faster (sometimes) but often makes them care less about the work

Sometimes using AI to help write code feels like a superpower (I say this from personal experience). You have a thought for a feature, you write a prompt, and you have a working version of it in minutes.

But how does this feel? It's a question I have been asking myself for a long time, and a big reason I proposed this workshop in the first place. For me, when I'm relying heavily on Co-pilot to write my code, I feel a far greater detachment from the final product.

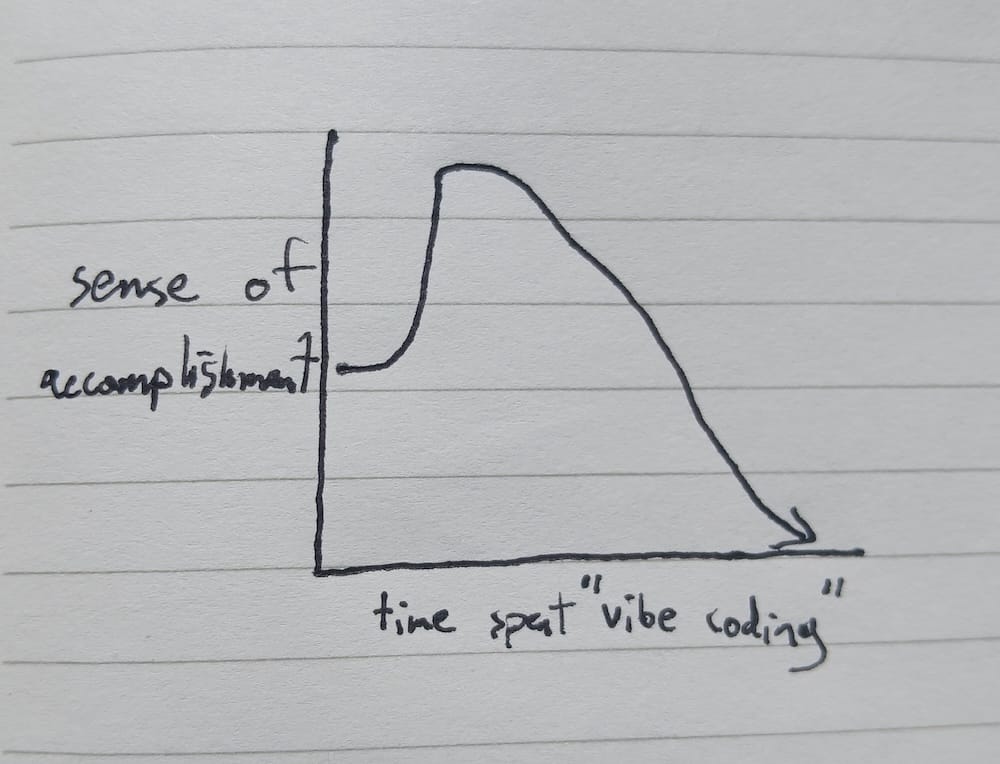

My trajectory seems to go something like this:

Immediate satisfaction, even a sense of wonder. Then a plateau. And then the gradual decline into "well, it's done now and it basically works". But does it feel like my work?

Now, this is going to give some real "back in my day" energy, but stick with me. When I started in data visualization, people were still learning from books. There were some incredible resources both online and off for learning D3.js. I read these books, I followed tutorials, and I build side projects until I understood how to bring an idea in my head to life on a screen.

Learning a very low-level and custom library like D3.js is, to put it plainly, a pain in the ass. But, when I got something to work after hours of debugging, and that custom data visualization appeared just as I sketched on paper, I felt like I had summited a mountaintop.

Now we spend all day riding gondolas up and down.

Relying so heavily on AI to do the work for us detaches us from the craft of making something. It removes friction. And friction can be deeply satisfying.

I'll end this reflection with a few comments (summarized) that I overheard while walking the room.

"I can build things faster, but usually I don't really know how or why they work."

"I feel like I dive into code prompting right away instead of thinking through my ideas and how they will actually play out first."

"I haven't written code myself in a long time and it makes me feel like I'm losing my sharpness."

Engineers do not feel hopeful about the future

I'm not going to lie, the "future" column of these murals was grim. Lots of uncertainty, lots of spiraling lines, lots of question marks. Here's an interesting observation—many people who used the green color for their data portrait (signifying that they felt overall the future was "bright") went the opposite direction when asked about their work as it relates to AI.

This is where the cognitive dissonance of the whole activity was on full display. Not one person in that room had bypassed using AI altogether. Many used it daily. And many talked about how their employers had made an intentional point to introduce it into their workflows.

But I didn't hear many positive comments about a future of coding with AI. Most people talked about a fear of replacement, a sense of being sidelined creatively, or being pushed more into a "machine manager" than an engineer.

Essentially, workers are using AI in their work, they don't love the direction it appears to be heading in, but they are afraid to stop using AI for fear of being left behind.

Where does this leave us?

My goal in this workshop was not to land on any answers. Actually that's probably the opposite of what I wanted to achieve. I wanted to give people, specifically people that work with data, a space and methodology to engage with complicated feelings.

Our data practices are so often entangled with binary thinking, fixed boundaries, and set scales. But that's not how we move through the world. I believe that complex topics, like how people feel about new technology, deserve an equally complex, imprecise, and subjective way of dissecting the source material. If you haven't already, I highly recommend the data humanism manifesto for more on this thinking.

As always, if you have any thoughts feel free to hit reply! More next time.

-ben